When we learn to make do

One Wednesday morning, in the fall of 1929, my 28 year old grandfather rolled out of bed in the house he was born in, a house that his grandfather built, in a fishing community called Arisaig, in Nova Scotia. He drew on a pair of wool pants, tucked in a cotton plaid long sleeve and ducked his head under the beam above the stairs.

This time of year, the fishing nets had been dried and cleaned, mended, and stored in piles above his father's forge. Crops were coming in, the second cut of hay gathered, and hardwood cut for winter heat and cooking. There was no electricity, no TV, no radio. Spirits were high, fine top hats hung on some antlers, and a China cabinet stood in the corner. Life was good.

Neighbours stopped by as usual. The homestead is near the wharf and the church, so Grandpa saw many of the same friends and neighbours every day. They talked about what was in the papers that morning. Stock markets were a world away from life there, then, but the shock of Black Tuesday travelled fast.

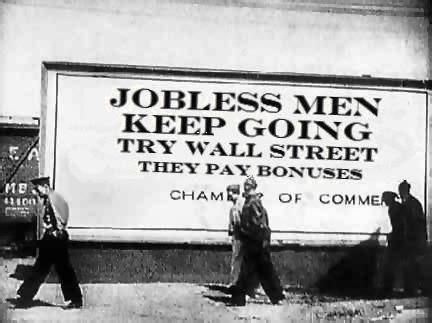

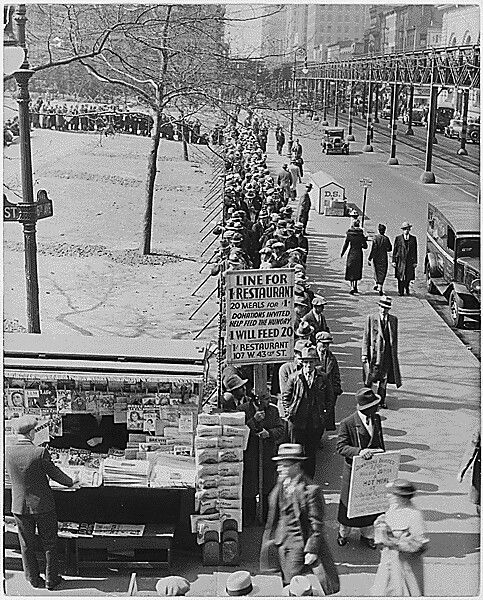

From a high on September 3, 1929, the stock market would lose 90% of its value by July 8, 1932, and not recover for 25 years. The crash destroyed confidence in the economy, sent commodities like gold soaring in value while the dollar collapsed, forcing the central bank to raise interest rates, which crushed the capital-intensive businesses of the industrial age that drove employment. The Great Depression had begun.

If you're one of the dozens☺of regular readers of these "weekly" musings, you may have noticed I missed last week. I blame my parents, who came to visit and distracted me.

My uncle, dad's brother, who I grew up working with, also came to visit - a real treat for me. It's from him that I picked up all these bad habits that consume my weekends and evenings: building stuff, fixing stuff, thinking about stuff to build and fix. So I got to show him all the trouble he's caused.

As they inspected our little farm setup, it started the brothers talking about growing up with parents who lived through the great depression.

Grandpa was a fisherman, like most dads there at the time, and brought plenty home: lobster, salmon, mackerel, even smelts. Their mother tended milking cows, made butter and cream, collected apples and berries, and was a phenomenal cook. There were chickens and pigs, and a large garden with mountains of potatoes, turnip, carrots, onions, beets and more.

Ironically, it sounds similar to what I'm attempting to do, a hundred years later, but not so much in any great depression. I might have to reflect on that!

The boys recalled what was bought from the grocer: flour, sugar, spices, salt, and pepper. That's it.

By the time I was growing up, my grandma had passed and Grandpa wore the Great Depression on his aged face. I remember the boys being frustrated finding cash, again, under his mattress. He'd ask my mom to mend the elbow of a shirt that had few threads left to connect, while a dozen new ones hung, unworn, in his closet. I remember him rowing the dory to the salmon net, dragging the outboard motor behind (though he gave in to that temptation as he and I aged and I begged to drive the stout, wooden dory). Little effort or money was spent on the unnecessary.

You'd forgive him if he was bitter, but my grandpa was really happy. He loved nature documentaries, like bears catching salmon at a waterfall. "Look, look, pretty smart, isn't he!" or stopping the car for a duck with ducklings in tow, "Nature's a wonderful thing, isn't it?"

It's nice to consider the apparent paradox of living as meagrely as possible while being truly happy. It feels relieving almost, like an assurance that we have the ability to calibrate to what we have. We can learn to make do. Maybe that's what "stop and smell the roses" and a thousand other clichés are about.

Thanks for reading. Send me an email anytime. You can peruse other musings of this wannabe farmer from the homepage, or click on my picture, below.